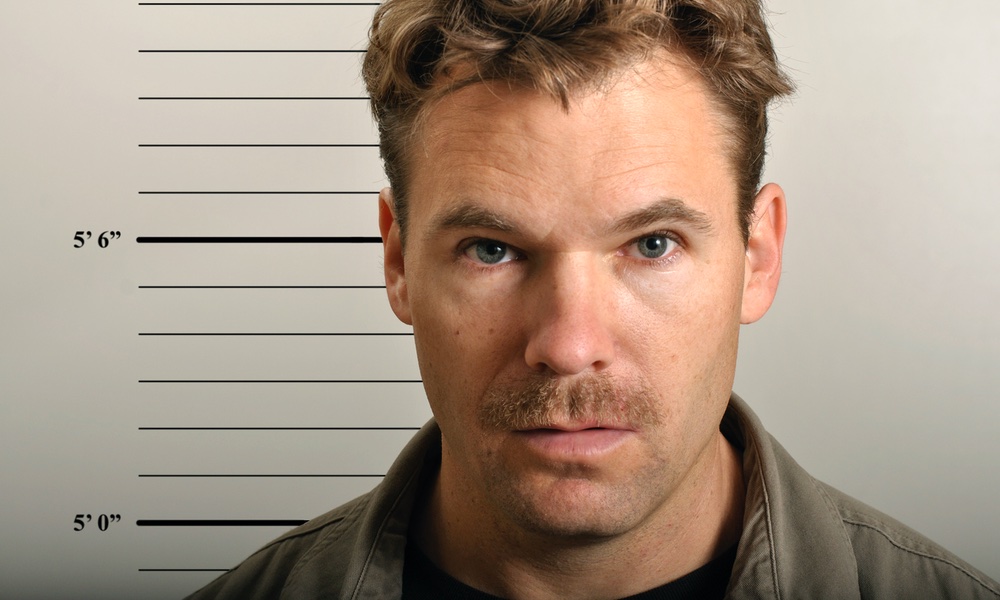

When eyewitnesses to a crime are brought in to pick a suspect out of a lineup, one photo of the suspect is displayed, plus photos of five or more “fillers” who are known to be innocent.

Usually, the people who serve as fillers are chosen because they look similar to the suspect, but researchers have recently found that eyewitnesses are better able to identify the suspect if fillers resemble a basic description of the suspect, but have faces that are less similar, rather than more, to that of the suspect.

This counterintuitive finding improved eyewitness performance by 10 percent.People were shown a mock-crime video of a white male stealing an office laptop. Then they were shown photographs of one suspect — either the perpetrator or an innocent suspect — and five fillers.

Participants in the study were shown a mock-crime video of a white male stealing an office laptop. Then they were shown photographs of one suspect — either the perpetrator or an innocent suspect — and five fillers. The men who were fillers always matched the most basic description of the perpetrator, but they varied in how much their faces looked like his. To determine facial similarity among the photos, an additional set of participants ranked the photos on a scale of 1 to 7, with 7 being most similar.

Eyewitnesses did a better job of picking out the perpetrator accurately when he was in the lineup with fillers who were facially dissimilar, the researchers found. Even better, the participants acting as eyewitnesses were not more likely to wrongly identify an innocent suspect when the real perpetrator was not in the lineup.

“In practice, police tend to err on the side of picking facially similar fillers for their lineups,” John Wixted, the paper's senior author and a professor in the University of California San Diego Department of Psychology, said in a statement. “What our study shows is that it is, contrary to intuition, actually better to pick fillers who are facially dissimilar. Doing it this way continues to protect the innocent to the same degree while helping witnesses to correctly identify the guilty more frequently.”

The idea behind the approach is based on signal detection, a way of measuring how accurately a signal, in this case, a suspect, is perceived or detected. Correctly detecting a signal that is really there is counted as a hit; missing a signal that is present is a miss. On the other hand, incorrectly detecting the signal or suspect is present when it’s not, is also a miss; while correctly determining that it is not present is also counted as a hit.

The study is published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.