If you live in a food desert, where it's tough, if not impossible, to get healthy fresh produce and non-processed foods, there's a good chance the community also has a high rate of obesity, along with the serious health issues that often follow, such as diabetes and heart problems.

Disadvantaged neighborhoods affect more than residents' waistlines, however. They can have a negative impact on the microstructure in the brains of people who live there, a new UCLA study finds.

A disadvantaged neighborhood is defined by a combination of factors such as low median income, low education level, crowding, environmental hazards and a lack of healthy food options.The brain suffers the consequences of living in a disadvantaged neighborhood. There's a disruption of flexibility of information processing in the brain that's specifically involved in reward, emotion regulation and cognition.

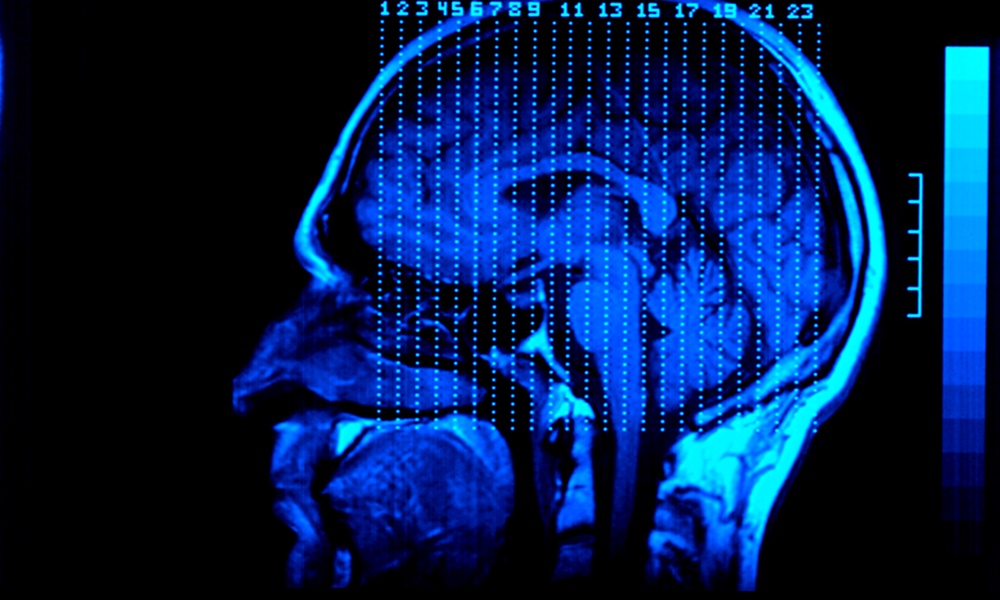

Ninety-two people — 27 men and 65 women — took part in the study. The participants underwent two types of MRI scans that, when analyzed, provided insights into the brain's structure, signaling (the ability to sense, interpret and ultimately act upon the environment) and function. The researchers used the Area Deprivation Index (ADI) which includes factors such as education, income, employment and housing quality.

“We found that neighborhood disadvantage was associated with differences in the fine structure of the cortex of the brain,” Arpana Gupta of UCLA's David Geffen School of Medicine, and senior author of the study, said in a press release. “Some of these differences were linked to higher body mass index and correlated with high intake of the trans-fatty acids found in fried fast food.”

While fresh produce is hard to come by in these communities, fast food restaurants that offer menus high in unhealthy trans-fatty acids are usually plentiful. The poor quality of available foods increases the intake of calories from ultra-processed foods high in trans-fatty acids.

The brain suffers the consequences of living in disadvantaged neighborhoods, as the study showed. Emotion regulation and cognition in the brain were disrupted and contributed to a lack of flexibility in information processing, particularly that involved in processing rewards.

“Different populations of cells exist in different layers of the cortex, where there are different signaling mechanisms and information-processing functions,” said the study's first author, Lisa Kilpatrick, a researcher in the Goodman-Luskin Microbiome Center focusing on brain signatures related to brain-body dysregulation. “Examining the microstructure at different cortical levels provides a better understanding of alterations in cell populations, processes and communication routes that may be affected by living in a disadvantaged neighborhood.”Fresh produce is hard to come by in these economically disadvantaged communities, but fast food restaurants that offer menus high in unhealthy trans-fatty acids are usually plentiful.

Disadvantaged communities can improve the health, brain activity and the overall wellbeing of residents. Stores and restaurants that offer fresh produce and nutrient-rich meals — rather than unhealthy and highly processed fast foods — are a good place to start. Improving schools and school access, transportation access, job creation and workforce development — all can directly or indirectly help to support these neighborhoods.

The study is published in Communications Medicine.