Old bones heal slowly because of inflammation, not age. That's what a new study strongly suggests. And while this may be of little immediate comfort to those with older, fragile bones, it does offer some hope because inflammation can be treated more easily than old age.

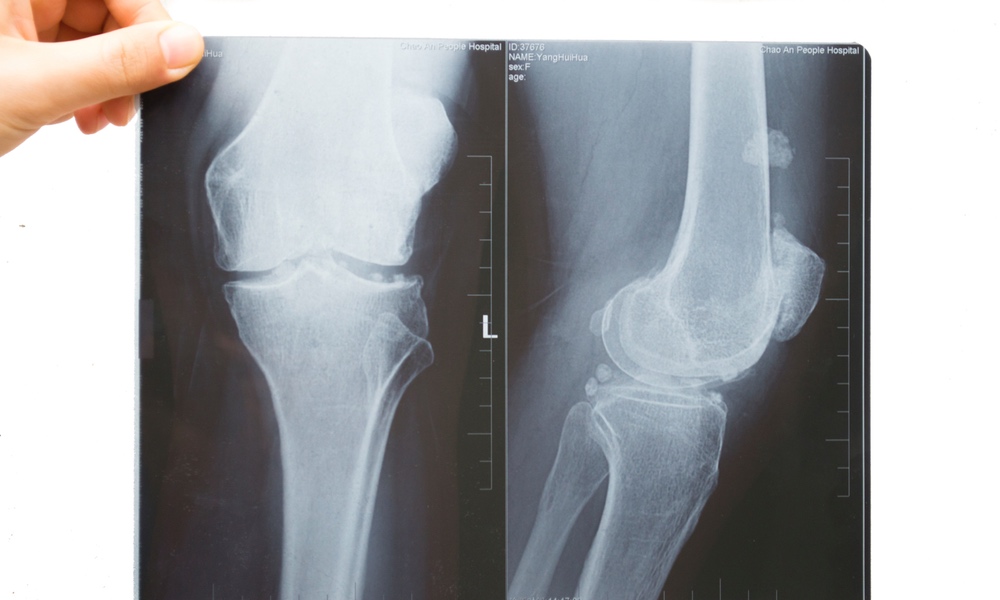

As people age, their bones become more porous and grow weaker, making them susceptible to fractures. And in the elderly, fractures mean more than just broken bones — the mortality rate for men in the first year after a hip fracture can reach as high as 37 percent.

It's not clear why a hip fracture should cause such a large spike in deaths, but it is certain that the best response is to stop bones from weakening in the first place, but that's easier said than done.Inflammation can be treated more easily than old age.

They suspected that some unknown factor circulating in the blood appeared to be responsible. When stem cells from young mice were exposed to the blood serum of older mice, they became four times less likely to divide and multiply.

They didn't find this unknown factor, but they did pinpoint how it works. It causes an increase in NFκB (NF kappa B), a protein that strongly stimulates the immune system. NFκB interacts with DNA to turn on several pro-inflammatory genes, which in turn cause skeletal stem cells to stop multiplying.

An inflammatory immune response is necessary to repel invading bacteria and other disease-causing organisms. But sometimes the immune system misfires, directing its attack at the body's own tissues, cells or proteins, as it does in rheumatoid arthritis. This is what appears to be happening in older bones.

Further experiments revealed that anti-inflammatory treatment with sodium salicylate, a chemical closely related to aspirin, repressed NFκB action, reduced chronic inflammation and increased the number of skeletal stem cells. It also altered the activity of thousands of genes in the stem cells, restoring their genetic profile to what's seen in young skeletal stem cells. In other words, some of the changes normally observed in elderly mice were not necessarily permanent.

An article on the study appears in PNAS.