A diet lacking in the amino acid, tryptophan, may set unhealthy changes in the microbiome in motion as we age. Inflammation, mood changes and sleeping problems could be among the effects of a tryptophan deficiency, a new study suggests.

Amino acids combine in various ways to make proteins in the body, and the way they are arranged determines their function — skin cell, blood cell, immune cell, and so on. Tryptophan is one of the nine essential amino acids. Essential means our body cannot make it; we must obtain it from supplements or the foods we eat. Milk, turkey, chicken and oats are some good sources of tryptophan.

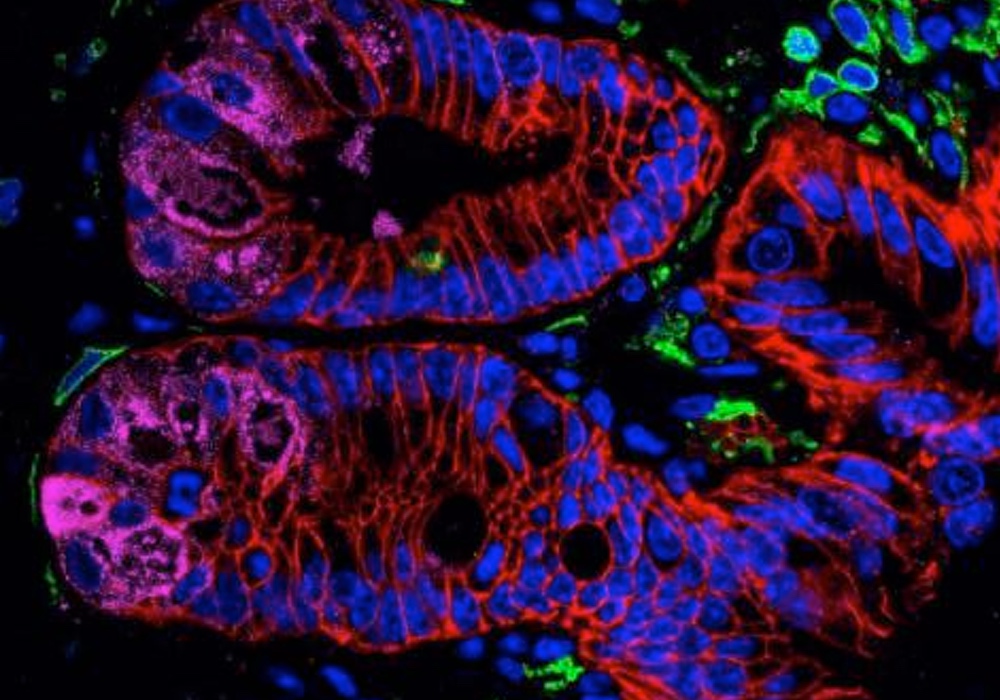

Bacterial cells are also made from amino acids. Trillions of bacteria make up the microbiome of the gut, and our diets have a lot to do with its health and, in turn, our body's well-being.Mice who ate the high-tryptophan diet had higher levels of a molecule that calmed inflammation.

When our microbiota is healthy, tryptophan helps in the production of the neurotransmitter serotonin, which reduces depression risk, and melatonin, which aids a good night's sleep, Sadanand Fulzele, one of the researchers, explained.

The team fed older mice three different diets for eight weeks — diets lacking in tryptophan, diets with sufficient tryptophan and diets high in the amino acid. After only eight weeks on a diet deficient in tryptophan, the mice showed unhealthy changes in the bacteria that make up the gut microbiome and high levels of inflammation.

Lower levels of the bacterium that helps metabolize tryptophan into serotonin, the “feel good” neurotransmitter targeted by many antidepressant medications were also seen, along with a substantial increase in a bacterium associated with intestinal inflammation.

On the other hand, mice who ate the high-tryptophan diet had higher levels of a molecule that calmed inflammation.

A healthy gut microbiome helps to ensure that tryptophan does good things for us such as producing serotonin that lowers the risk of depression and melatonin that helps us sleep well. As we age, this system may go awry though.Milk, turkey, chicken and oats are some good sources of tryptophan.

“We think the microbiome plays an important role in the aging process and we think one of those players in the aging [process] is tryptophan, which produces metabolites that affect every organ function,” researcher, Carlos M. Isales, of the MCG Center for Healthy Aging, said in a statement. “We also have evidence that the composition of the bacteria that utilize tryptophan changes so even if you eat more tryptophan, you may not use it correctly.”

There are tryptophan supplements, but they should only be taken in consultation with your doctor. They can cause a serious imbalance in serotonin among people on antidepressants or taking St. John’s Wort for depression. The supplement, L-tryptophan, was banned for time in the late 1980s when tainted tryptophan supplements were believed to be behind a surge in a life-threatening condition, eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome (EMS), among many people taking it.

The study is published in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences.