The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recently lowered the age at which people at average risk for colorectal cancer (CRC) should start getting screened — from age 50 to age 45. Its recommendation for periodic CRC screening for older people, those up to age 75, did not change, nor did its recommendation that screening decisions for adults aged 76 to 85 years should be based on a consideration of a person’s overall health and the results of earlier screenings.

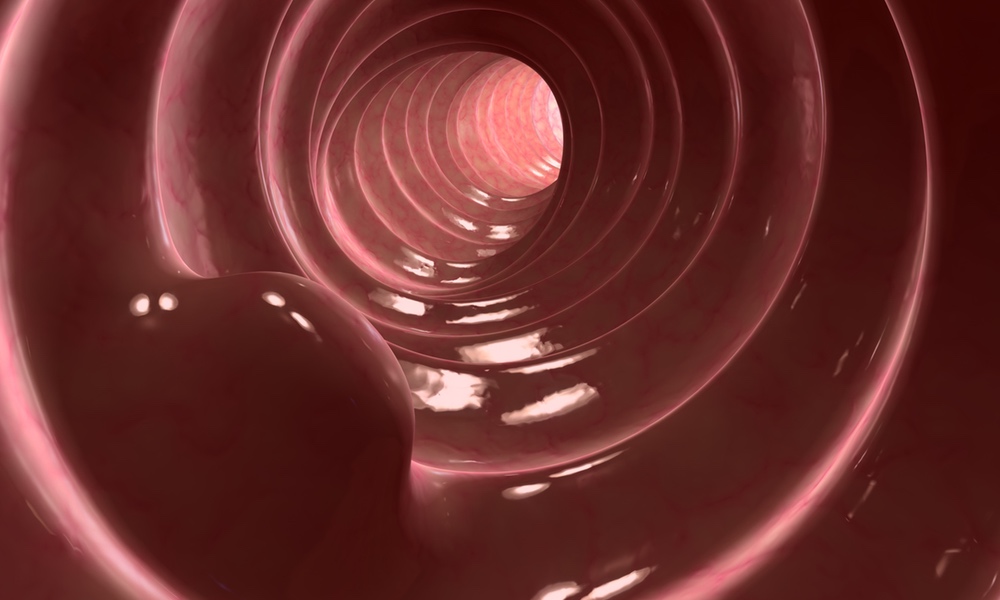

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer death in the U.S. Screening endoscopy, via either sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy, can detect precancerous lesions or CRC in an early, treatable stage.

In addition to the USPSTF guidelines, other guidelines also do not recommend continued screening beyond the age of 75 years or when life expectancy is less than 10 years because there has been little evidence for the benefit of continuing CRC screening after age 75.Those who were screened for the first time only after they turned 75 had a 49 percent reduced incidence of CRC and a 37 percent reduced risk of death, compared to those who were never screened.

The researchers analyzed data on the history of CRC screening of the more than 56,000 participants who turned 75 during the 28-year study period. The participants were part of two large studies: the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study and the Nurses’ Health Study. Participants in both studies had filled out questionnaires every two years about lifestyle, health history, screenings and disease outcomes.

Just over 660 cases of CRC were diagnosed from this data, and about 320 deaths from CRC occurred among participants after age 75. The study found that CRC screening after age 75 was associated with an almost 40 percent reduced incidence of CRC and a 40 percent reduced risk of death from CRC, whether or not participants had been screened before they turned 75.

Among those who were screened before age 75, screening after they turned 75 reduced their incidence of CRC by 33 percent and their risk of death from CRC by 42 percent, compared to those who were not screened before age 75. And those who were screened for the first time only after they turned 75 had a 49 percent reduced incidence of CRC and a 37 percent reduced risk of death, compared to those who were never screened.

Screening did not reduce the risk of death from CRC among those with cardiovascular disease or multiple chronic health problems such as diabetes, high cholesterol or hypertension. “The key take home message,” said Chan, chief of the clinical and translational epidemiology unit at Massachusetts General Hospital, “is that CRC screening should be tailored to individual risk factors.”

The study and a related editorial are published in JAMA Oncology.