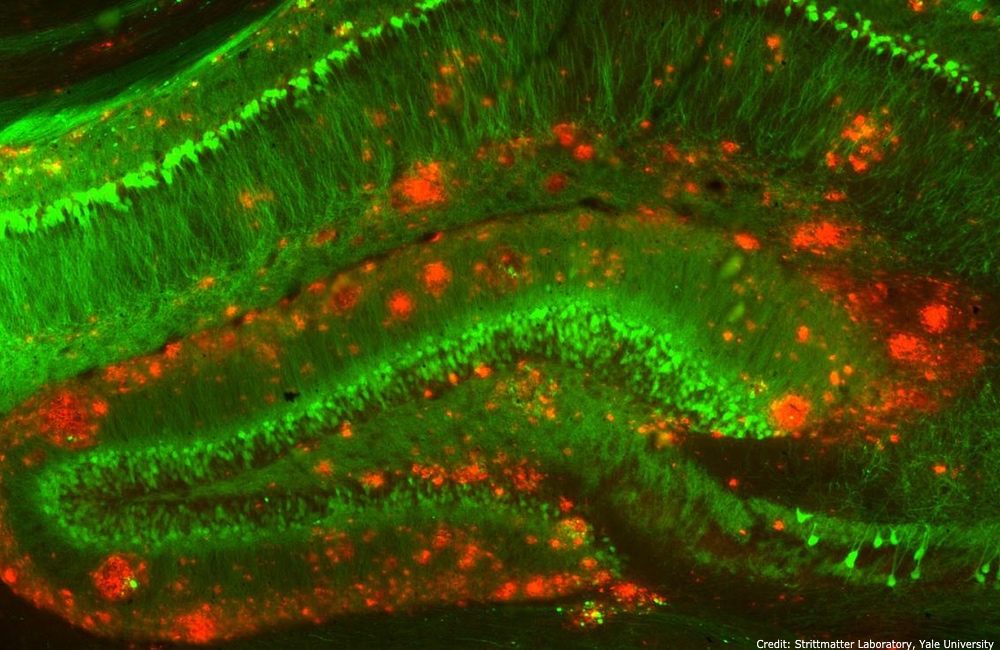

The future of Alzheimer’s treatment could be a drug that targets the brain’s waste removal process. The drug targets neuron cells known to be a key factor in the development of the disease and the process by which the body identifies and cleans out waste proteins surrounding neuron cells in the brain.

Alzheimer’s disease is caused by a buildup of waste proteins in the brain’s cells. These proteins form plaques along neuron cells that slow the processing of information. Over time this process causes changes including loss of memory, confusion, irritability and motor control issues. One in three American seniors will die with Alzheimer’s or some other form of dementia.

The experimental drug's waste-clearing effectiveness was first confirmed by a research team at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine led by Ana Maria Cuervo, the scientist who discovered and named the waste-removal process, known as chaperone-mediated autophagy or CMA.The brain’s CMA trash-removal system naturally declines by about 30 percent as people approach their 70s and 80s. While most people’s brains can adapt to this change, in those with neurodegenerative disease the decline appears to set off a vicious cycle.

The team is optimistic that there's a good chance the results will translate to similar benefits in people, even though the utility of mouse-based trials to predict outcomes in people is not always assured, particularly for Alzheimer’s treatments. The group's research over the years had determined that impaired CMA was a key factor for developing Alzheimer’s in mice, and then they subsequently found that the same process operated in people with the disease.

Because the causal links between CMA and Alzheimer’s have been proven, the belief is that by encouraging waste removal in cells, the course of disease can likely be slowed and even reversed.

“We were encouraged to find in our study that the drop-off in cellular cleaning that contributes to Alzheimer's in mice also occurs in people with the disease, suggesting that our drug may also work in humans,” Dr. Cuervo, the Robert and Renée Belfer Chair for the Study of Neurodegenerative Diseases, said in a statement.

Even mice with signs of advanced neurodegenerative disease — such as trouble walking — showed significant improvement following treatment with the new drug, a finding that sparks hope for the future of Alzheimer’s treatment in people already in early to moderate stages of the disease.

A person’s risk for developing Alzheimer’s can be influenced by genetics, but lifestyle choices can also play a big part in preventing the development of the disease. Diet and regular exercise, as well as avoiding alcohol and smoking, can also keep the brain healthy.

The study is published in Cell.