There are millions of people living with Alzheimer’s around the world, and this makes understanding the origins of the disease critical. And though there’s still a lot we don’t know, a new study adds a big and important piece to the puzzle, finding that part of what may set the brain up for Alzheimer’s is a virus that many people are exposed to in childhood.

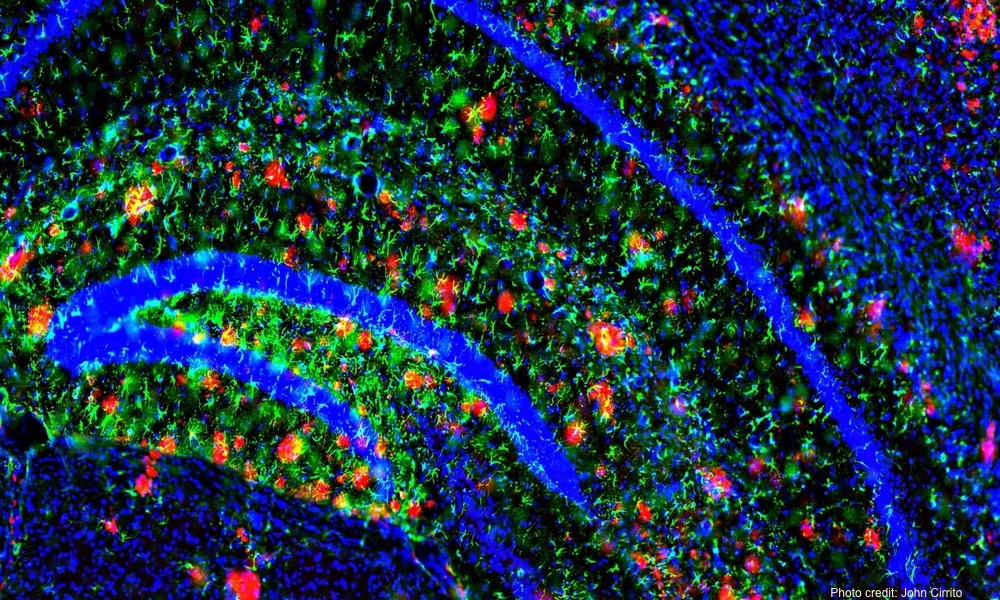

Researchers looked at information collected on over 900 brains that had been donated to research. Six hundred of the brains had Alzheimer’s, and 300 were healthy. The data on each brain included DNA and RNA information and, importantly, the genes that had been inherited and those that were turned on or off throughout life — that is, the epigenome.

The team also had behavioral and cognitive information from the person’s lifetime. In the case of the brains of those with Alzheimer's, the patient records included data on the severity of the amyloid-beta plaques and tau protein tangles that are hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease.“We didn't go looking for viruses, but viruses sort of screamed out at us.”

The team wasn’t specifically looking for viruses, but the data confirmed it in multiple tests. “We didn't go looking for viruses, but viruses sort of screamed out at us,” said author Ben Readhead. People are often exposed to HHV in childhood and, according to the paper, most don’t experience any significant issues from it. It can cause a condition called roseola, which can manifest as fever and a rash, or bring no symptoms at all.

The obvious question is whether the herpesvirus actually triggers the development of Alzheimer’s disease or if it’s the other way around — that a brain that’s already susceptible allows the virus to enter.

The team looked further and found something striking: that HHV genes appear to interact with genes that are known to be involved in Alzheimer’s risk. It may be that the virus can turn on or off these "Alzheimer's" genes. It may also be the plaques and tangles develop as the unfortunate fallout of the process of fighting the virus. It will take more investigation before researchers can say for certain how all the elements interact. But this study is the first to really support a viral theory of Alzheimer’s.

“This analysis allowed us to identify how the viruses are directly interacting with or coregulating known Alzheimer's genes,” says study author Joel Dudley. “I don't think we can answer whether herpesviruses are a primary cause of Alzheimer's disease. But what's clear is that they're perturbing and participating in networks that directly underlie Alzheimer's pathophysiology.”It may be that the virus can turn on or off the genes known to play a role in Alzheimer’s, or the plaques and tangles develop as the fallout from fighting the virus.

The authors hope that understanding the processes more fully may lead to new and more effective treatments. Once-promising Alzheimer’s medications have failed to perform in clinical trials. So the idea that a childhood virus could set the stage for plaques and tau protein tangles to follow, rather than discouraging hope, opens possible new paths to prevent or treat this devastating disease.

The research was carried out by scientists at Arizona State University-Banner Neurodegenerative Disease Research Center (NDRC) and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. It is published in the journal Neuron.