Many of the long-term symptoms people who have had COVID-19 suffer from, such as myalgia and fatigue, are commonly associated with autoimmune disorders.

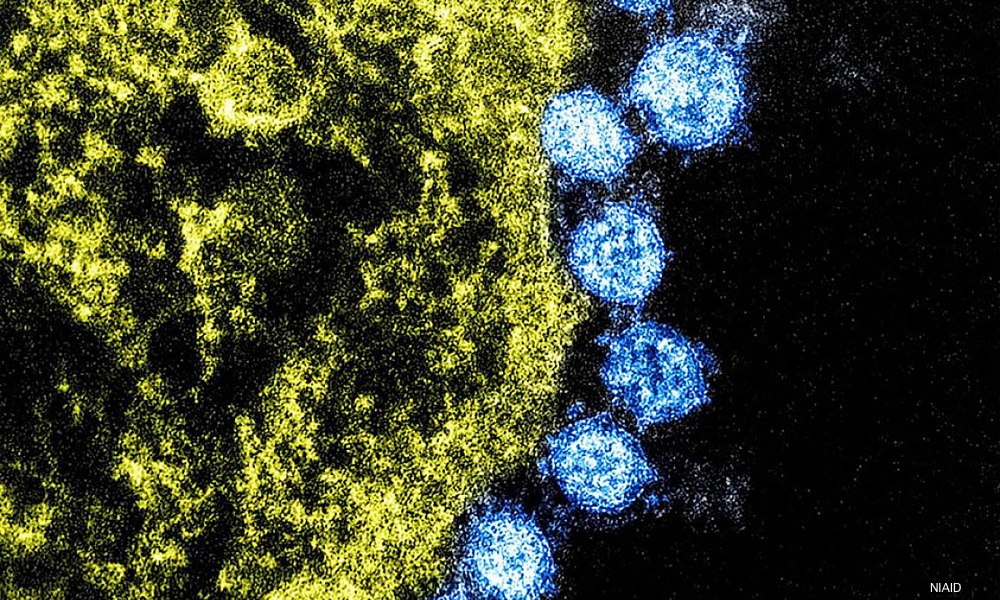

There’s a good reason for this, a new study led by scientists at Stanford University found. Autoantibodies found in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 appear to be targeting patients’ own tissues, and this is often a precursor to autoimmune disease.

“If you are sick enough to be hospitalized with COVID-19, you may not be out of the woods even after you recover,” PJ Utz, senior corresponding author on the study said, adding that the findings of the current study support the value of getting vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.People who are vaccinated and quickly mount a response to the SARS-CoV-2 viral spike protein should be less likely to develop autoantibodies and so be less likely to develop long-term, COVID-related autoimmune disorders.

Serum from 147 patients hospitalized for COVID-19 and 48 patients with COVID-19 at Kaiser Permanente was analyzed, and serum drawn prior to the pandemic from 41 healthy blood donors was used as a control. The researchers measured levels of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2; autoantibodies directed at patients’ own tissues; and antibodies against cytokines, proteins immune cells secrete that enable them to communicate with each another and work together.

Sixty to 80 percent of hospitalized COVID patients had at least one anti-cytokine antibody, compared to about 15 percent of healthy controls. The researchers believe this might be the result of an overactive immune system triggered by a virulent infection with SARS-CoV-2. “The abundance of cytokines may trip off the erroneous production of antibodies targeting them,” Utz said.

If these antibodies prevent cytokines from binding to the appropriate receptors on target immune cells, those immune cells will not be activated. Failure to activate immune cells could allow the virus to replicate, and result in more serious COVID-19 outcomes.

Paired blood samples drawn on different days were available for 48 patients. Samples from 21 of these patients were analyzed to see if the number of autoantibodies changes over time. During the course of a week, starting from the day they were admitted, 18 of the 21 patients had an increase in the number of autoantibodies. “In many cases, autoantibody levels were similar to what you’d see in a diagnosed autoimmune disease,” said Utz, a professor of rheumatology and immunology at Stanford Medicine.

Autoantibody overproduction could also be the result of exposure to viral material similar to human proteins, Utz said. “In a poorly controlled SARS-CoV-2 infection, when an intensifying immune response breaks down viral particles, the immune system sees viral particles it hasn’t seen before,” Utz explained. “If any of these particles resembles one of our own proteins, it could trigger autoantibody production.”About 60 to 80 percent of hospitalized patients had at least one anti-cytokine antibody, versus about 15 percent of healthy controls.

Going forward, Utz said he plans to study blood samples from people who were infected with SARS-CoV-2 but who were asymptomatic or had mild symptoms. These people do not experience hyperactivation of their immune system, so studying their blood samples could determine if a hyperactive immune response or the similarity of viral proteins to human proteins causes autoantibody production.

The study is published in Nature Communications.