It has been over 50 years since a mandatory shift to daylight saving time in the spring and a return to standard time in the fall became law. States were allowed to opt out of it and remain on standard time year-round, but only Hawaii and Arizona (except for the Navajo Nation) have chosen to do so. Switching to year-round daylight saving time is not allowed. That would require a change in federal law. So in most states, people reset their clocks twice a year.

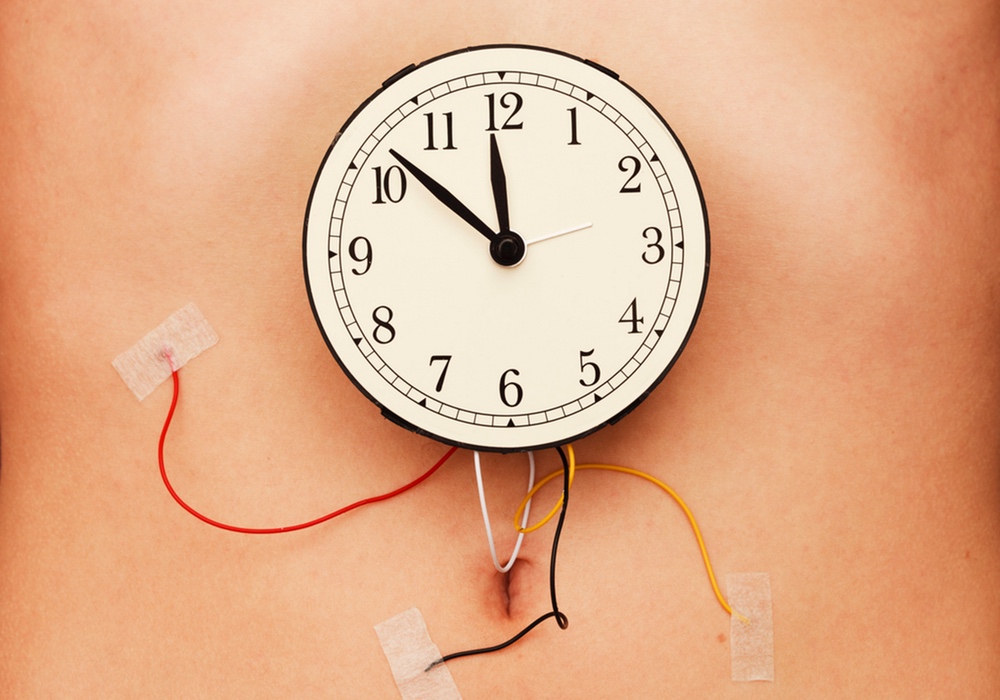

Turning clocks back in the fall isn't so bad. It's nice to gain an extra hour of sleep, though it can still take a while to adjust to the change. Setting the clocks ahead every March is a different story. It isn't only unpopular; it may have serious health effects.

How much do people dislike doing this? Over 30 states have introduced bills at one time or another to do away with bi-annual clock changes. Several states have even passed legislation that would make daylight saving time permanent, though that can't take effect without congressional approval. Some people like daylight saving time because it stays light later in the day, saving energy and possibly cutting crime. Others hate it because their children have to set out for school while it's still dark outside. But nobody seems to like changing the clocks twice a year.One study found a rise in strokes occurring in the first two days after the clocks are set forward; another found an increase in heart attacks.

The clock by your bedside may say 8 am, but the clock in your brain knows it isn't.

In a Viewpoint published in JAMA Neurology, she and her colleagues, from Vanderbilt and the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, outlined some of the evidence that the springtime switch has important health consequences. One study found a rise in strokes occurring in the first two days after the clocks are set forward. Another found an increase in heart attacks in the two weeks following the spring change. Though the increase was small (five percent), it was statistically significant. And a study of high school students before and after the spring switch reported them getting, on average, over half an hour less sleep in the week after the change was made, something no one needs in our sleep-deprived society.

All the studies suggest that setting the clocks forward increases stress, an increase that manifests itself in various unhealthy ways.

What's the solution? A close look at the various proposals passed and under consideration by state legislatures shows a definite lack of consensus. Some states are hoping to do away with changing the clocks; some are considering permanent daylight savings time, others a permanent standard time; and still others are studying the issue and looking at other options. But it's pretty clear that most would like to find a way to stop switching the clocks twice a year.

The article on the health effects of changing the clocks appears in JAMA Neurology.