Aromatase inhibitors are often used to treat and prevent recurrences of hormone-sensitive breast cancer in post-menopausal women. These drugs, such as Arimidex (anastrozole), Aromasin (exemestane) and Femara (letrozole), stop the production of estrogen in peripheral tissues such as the fatty tissue of breasts. They may be prescribed to women for as long as ten years.

Unfortunately, as many as half the women who take these drugs experience joint pain and stiffness, which may be debilitating enough to lead them to discontinue treatment, raising the risk of a recurrence of the breast cancer. The side effects are serious and common enough that they have a name — Aromatase Inhibitor Associated Musculoskeletal Syndrome (AIMSS). While some medications including opioids or duloxetine may be effective in relieving symptoms, these drugs often come with their own side effects or concerns with addiction.

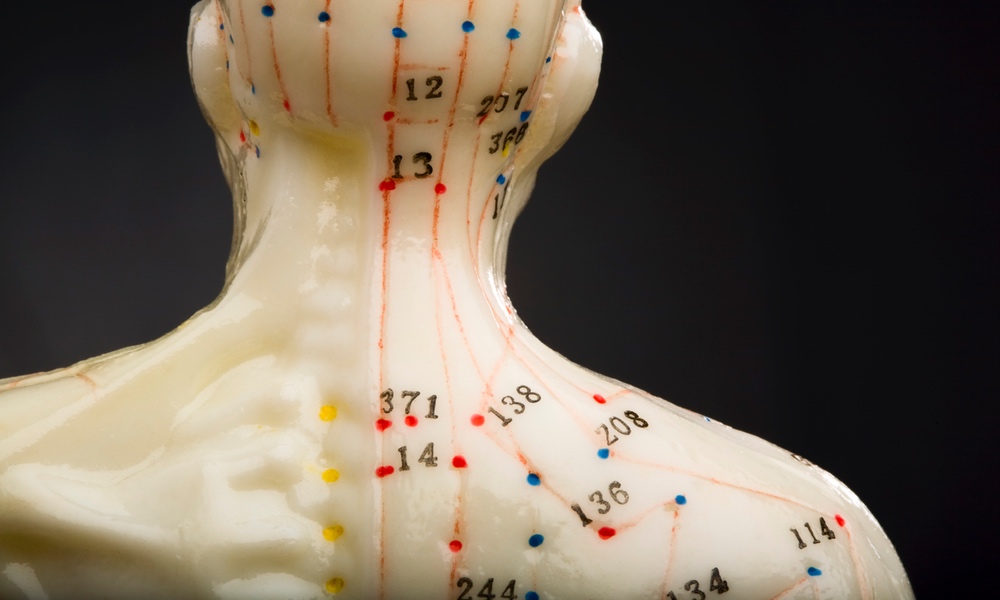

Researchers have looked for non-pharmacologic ways to treat the symptoms of AIMSS, and a recent presentation at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium highlighted the successful use of acupuncture for this purpose.The patients receiving the true acupuncture showed less pain than the other two groups, and their relief lasted for 24 weeks.

The results are promising for women with breast cancer. The patients receiving the true acupuncture showed less pain than the other two groups, and their relief lasted for 24 weeks. After the first six weeks, 58 percent of women in the real acupuncture group experienced at least a 50 percent reduction in pain, compared to 33 percent in the sham acupuncture and 31 percent in the group without treatment. Mild bruising at the site of the acupuncture needle insertion was the main side effect. Bruising was seen in both the true and sham treatment groups.

While additional research is needed on maintenance and boosters treatments, the investigators call for more consideration of acupuncture by patients and medical practitioners, and hope the results will encourage insurers to pay for treatment.

“This work strongly shows that true acupuncture results in better outcomes for women,” said Katherine Crew, an Associate Professor of Medicine and Epidemiology at the NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center and a co-investigator on the study team. “I expect this work to influence medical practice, as well as insurers’ willingness to reimburse for acupuncture during AI[MSS] treatment.”

The study was presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS) 2017.