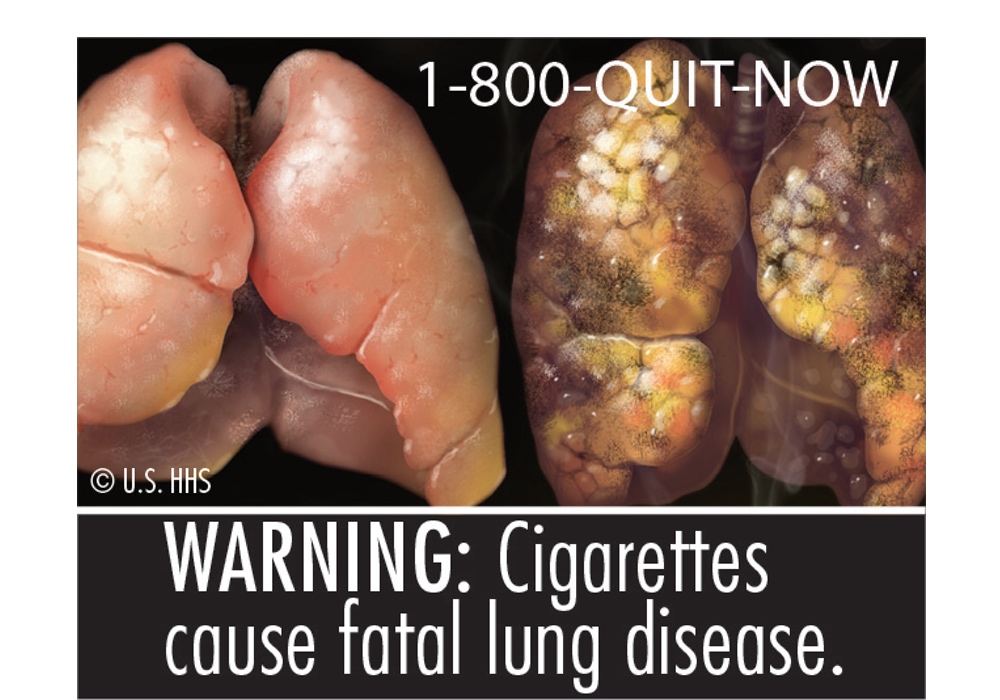

Cigarette packs in the United States were supposed to get vivid picture warnings — until a 2012 lawsuit stopped them from appearing. The warnings were designed to give smokers food for thought by showing graphic images of the consequences of smoking cigarettes, such as a photo of a man with a tracheotomy or the photo above of healthy versus diseased lungs.

Had the warnings become reality, a new study estimates that they would have reduced total smoking by 5% in the short term and 10% in the long term, and saved well over half a million lives in their first 50 years.

At least 77 countries now require graphic warnings on cigarette packages. They've been around long enough to get some idea of how effective they are or might be.These effects may seem modest in size, but they could be seen in less than a month.

Using information from those studies, as well as others and a computer model called SimSmoke that estimates the effect of future smoking policies based on the effect of past ones, the researchers estimated the effects graphic cigarette warnings would have on smoking in the U.S.

Along with the reductions in total smoking, they estimated that if implemented now, the warnings would reduce the number of deaths caused by smoking (from heart disease, lung cancer, etc.) by 652,800 by 2065. They would prevent more than 46,600 cases of low-birth weights, 73,600 cases of preterm birth and 1,000 SIDS deaths.

Another study published earlier this year tested the effect of graphic warnings on smokers more directly.

Smokers from North Carolina and California were randomly assigned to receive either text-only or four of the FDA's original nine graphic warnings on their cigarette packs for four weeks. Surveys were administered at the start of the study and at each weekly visit. Nineteen hundred smokers completed the study.

Perhaps more importantly, nearly 6% of smokers who received pictorial warnings were able to quit smoking for at least a week by the end of the trial, compared with 3.8% of smokers who received text-only warnings (a 50% relative increase).

These effects may seem modest in size, but they could be seen in less than a month.

The 2012 court decision that stopped graphic warnings from being used was based on the view that the FDA had “not provided a shred of evidence” that these warnings reduce smoking. These two studies should help overcome that reservation.

An article on the SimSmoke study appears in Tobacco Control. The study on North Carolina and California Smokers appears in JAMA Internal Medicine.