Researchers have succeeded in re-growing hair in badly balding mice. While it's not clear yet if this will be helpful for people, the effect is striking (see image).

The uncertainty stems both from the fact that mice are not people and from the fact that these were highly unusual mice: they were genetically altered to produce extremely high levels of stress hormone.

The re-grown hair was 'largely retained' up to the study's end, four months afterward. This is a major portion of the mouse lifespan, which is under two years.

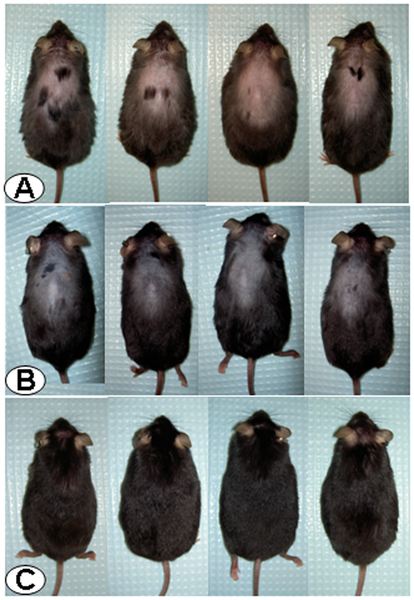

The hair re-growth was an accidental discovery. It was the byproduct of a joint UCLA/Veterans Administration research project designed to measure the effect of stress on the gastrointestinal system. The overstressed mice used in the study had all lost a large patch of hair from their back. During the study, the researchers noticed that their treatment had caused substantial hair re-growth — so much that the mice could not be distinguished from their non-stressed counterparts. The re-grown hair was "largely retained" up to the study's end, four months afterward. This is a major portion of the mouse lifespan, which is under two years.

In this study, the researchers treated the mice with a compound called astressin-B. This compound binds to the same receptor as CRF, essentially blocking and neutralizing the CRF. Mice were given intraperitoneal injections of astressin-B for five consecutive days to study its effects on gastrointestinal stress. The mice were then put back into a communal cage along with the other normal, non-stressed mice.

Three months later, the researchers wanted to perform further studies on the stressed mice. And they noticed that they could no longer distinguish the stressed mice from the normal mice by sight. The missing hair of the stressed mice had all grown back, totally covering the bald patch. The stressed mice had to be identified by their ear tags.

Photographs: Row A: Male CRF-OE mice (4 months old) injected ip once daily for 5 consecutive days with saline at 3 days after the last injection and Row B: astressin-B (5 μg/mouse) at 3 days after the last ip injection, and Row C: the same mice as in the middle panel Row B at 4 weeks after the last ip injection.

Further experiments showed that the hair had largely grown back three days after the last injection and fully grown back four weeks after the last injection (see image). And young genetically stressed mice given the injections never developed bald patches.

Stress is known to play a part in hair loss. What isn't known is whether this treatment will be useful in people or even in mice with normal stress hormone levels.

But in an article published by the New York Times on February 16, Dr. George Cotsarelis, chairman of the dermatology department at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, cautioned that the hair growth cycles are very different in mice and humans, so one could draw only limited conclusions from the research. Dr. Cotsarelis said that any treatment developed from the research would probably be useful only for hair loss specifically related to stress, like that caused by one-time events.

Right now no one knows for sure.

The researchers' article was published February 16, 2011 in PLoS ONE and is freely available.