Not everyone suffering from depression has been able to find relief using the neuroleptic drugs that have been developed since Prozac revolutionized treatment in the 1980s. Others have been reluctant to use antidepressant medications because of the side effects associated with them. Severe depression is debilitating and can end lives, so there is a continued push to find new treatments with fewer side effects to help those with treatment-resistant depression.

Recently transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS has been shown to benefit some with depression. A small study using an accelerated form of Intermittent theta-burst stimulation (iTBS), a noninvasive brain stimulation treatment that has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, yielded spectacularly successful results. Researchers at Stanford University tested a form of iTBS that relies on faster and more frequent pulses called Stanford Accelerated Intelligent Neuromodulation Therapy (SAINT).

“Patients that have been suffering from depression for 20-30 years were in this trial and after the 5-day SAINT protocol were able to reduce their symptoms to the point that their depression was in remission,” Keith Sudheimer, one of the authors, told TheDoctor.

The still-experimental approach offers hope to those for whom other treatments have not worked, particularly people troubled by repetitive thoughts of suicide. “Suicide and suicidal ideation is the biggest and most imminent threat to the well-being of patients with depression,” Sudheimer added. “Consequently we worry about it quite a bit and look for ways to resolve it as quickly as possible. SAINT seems to be effectively treating suicidal ideation at the same time as we treat the other symptoms of depression.”Scientists have been “eavesdropping” on the brain a long time, and studies like this one improve researchers’ ability to interpret the brain's language.

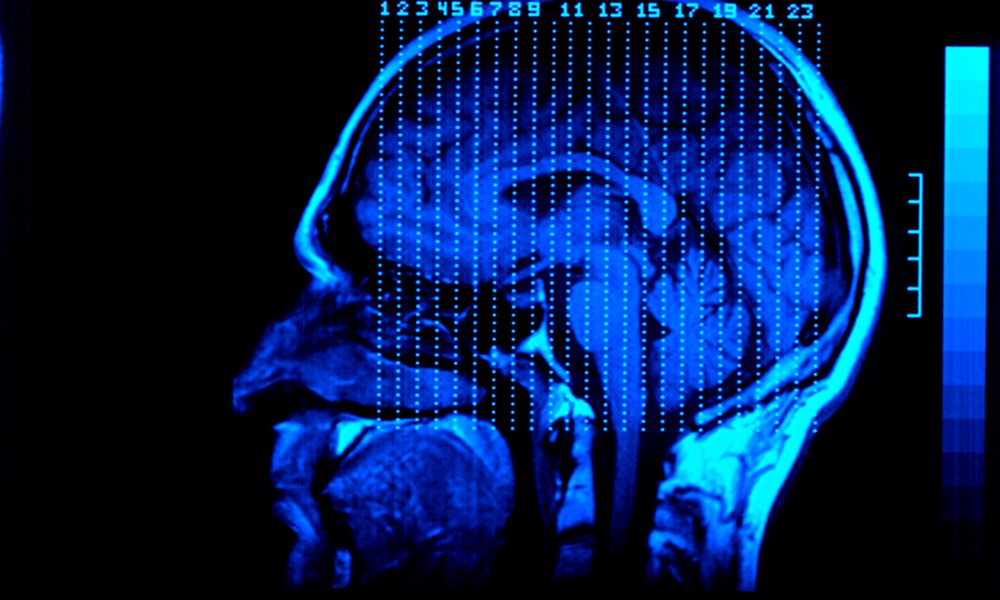

The team used pulses from MRIs spaced at 1,800 pulses per session, 10 times a day spaced 50 minutes apart, over five days to tap into an individual’s neurocircuitry. The MRIs targeted a part of the brain, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), associated with cognitive flexibility, working memory and abstract reasoning. Only one participant of an original group of 23 dropped out, due to anxiety, and another was disqualified for having a very high motor threshold (which is related to detecting twitching during an MRI). Each participant had suffered from either bipolar or major depressive disorder for many years.

But why pulses?

“The brain speaks to itself in a language we don’t entirely understand,” said Sudheimer, a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Stanford. “However, we do know a few things about the language. The frequency of neurons firing is important; the phase delays between neurons firing is important; and the spatial organization of brain activity (which brain regions are sending information where) is important.”

Researchers have been “eavesdropping” on the brain a long time, he explained, and studies such as these, in addition to helping patients, inform researchers’ ability to interpret that language. Sudheimer is hopeful that their results will advance our ability to help regulate activity in emotional brain areas that are hyperactive in depression.

The participants suffered no ill effects from the MRI treatment. Overwhelmingly, 90 percent were less depressed at the end of the study.

“We suspect that our results would not have been as good if we had not targeted the right spatial location or if we had sent the message using a pulse sequence that the brain did not recognize,” said Sudheimer. The placebo effect can lead researchers to overestimate how effective a treatment is, but Sudheimer and his colleagues feel confident in the results.

Getting an MRI isn’t fun and can be kind of boring, he said, but if it becomes as common to get one for depression as it is to have an x-ray for a broken leg, he sees its popularity growing.

The study is published in the American Journal of Psychiatry Online.