Ever since you lost your job, your stomach is in knots. It feels like you have a big interview approaching, but there is none. You aren’t sleeping well at night, waking up every couple of hours for no particular reason. And in the morning, you don’t feel rested. Your lower back hurts periodically and you’ve been getting sick more often than your friends have this season. (And speaking of your friends, they’re getting frustrated by your escalating moodiness.) You’re starting to wonder what’s wrong with you!

Though the word is thrown around a lot these days for obvious reasons, the reality is that stress can become a serious physiological and psychological problem if left untreated over the long term.

Technically, you’re not suffering from any major disease, but you have fallen victim to what an increasing number of people are suffering from these days – chronic stress. Though the word is thrown around a lot these days for obvious reasons, the reality is that stress can become a serious physiological and psychological problem if left untreated over the long term. Though the stress response actually serves a very important purpose, both evolutionarily and in the present day, a problem develops when feelings of stress become chronic – longstanding and unrelenting.

Feeling stressed all the time can make you depressed, cause weight gain, heart disease, memory loss, and sleep problems. It can interfere with sexual pleasure and may affect fertility. The following is a portrait of stress and its effects on various systems in the body, which can in turn affect your behavior and health. Knowing what stress does to your body is a first step in beginning to loosen its grip.

Stress becomes a problem rather than a life−saving response when the brain is deluged with stimuli that it perceives as repeated threats over a long period of time. And this is when stress morphs from an acute response to a specific threatening situation to chronic, a generalized feeling that the daily pressures of life constitute a threat, thus leading to many of the health concerns described above. Work, money, marital and health problems, and the pressures of parenthood are all perceived by the brain as significant stressors, and all elicit the stress response which affects both body and mind. Stressors include any stimulus that triggers the stress reaction, from the physical (for example, a car accident) to the emotional/psychological (e.g., a divorce or serious health problem).

Work, money, marital and health problems, and the pressures of parenthood are all perceived by the brain as significant stressors, and all elicit the stress response which affects both body and mind.

What happens physiologically during this reaction? The stress response is governed by the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which takes care of the many bodily processes that are “subconscious” or outside of conscious control. This system is charged with increasing heart rate, blood pressure, and blood sugar, and suppressing the digestive, reproductive, and immune systems – in short, readying the body to pour its resources into reaction, and rather than wasting valuable energy on extraneous activities like ovulation and digestion.

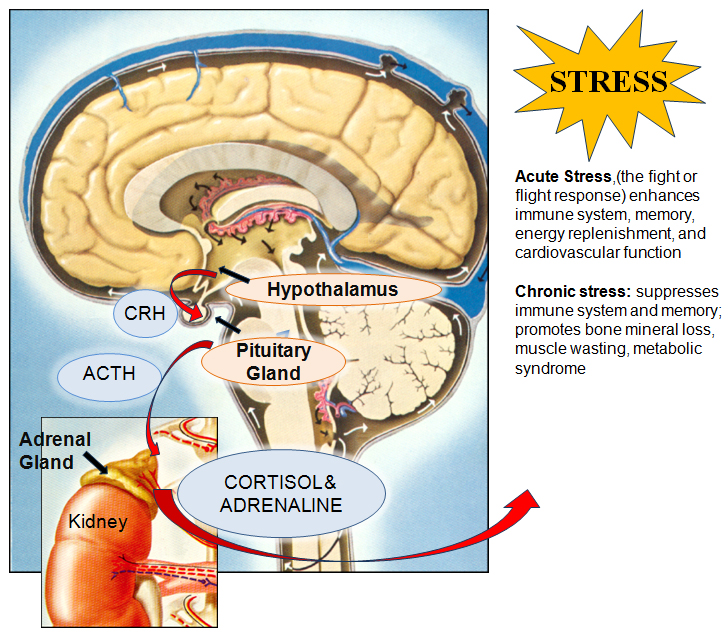

On a smaller level, the stress response is controlled by the hypothalamic−pituitary−adrenal (HPA) axis, illustrated in the Figure below. During this reaction, the hypothalamus (a brain structure involved in regulating basic body functions, like stress, sleep, sex, body temperature, and hunger) perceives a stressful stimulus from the outside world, and releases a hormone called corticotrophin−releasing hormone (CRH). This hormone signals the adjacent pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which travels through the blood to the adrenal glands, which sit on top of each kidney. Adrenocorticotropic hormone simulates the adrenals to release the two major stress hormones, adrenaline and cortisol. It is these two hormones that ready the body for reaction during the fight or flight response. The main function of adrenaline is to increase heart rate and blood pressure: in our evolutionary example above, it prepares the body to kick into high gear almost instantaneously. The effects of cortisol are observed over the longer−term: not only does the hormone increase blood pressure, but it increases blood sugar and mobilizes fat and protein stores to help replenish lost energy gradually as it is needed.

When confronted with a stressful stimulus from the outside world, the hypothalamus releases corticotrophin−releasing hormone (CRH). This hormone signals the adjoining pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which travels through the blood to the adrenal glands (which sit on top of each kidney), and release the two major stress hormones, adrenaline and cortisol. It is these two hormones that together elicit and maintain the body’s fight or flight response. Adrenaline helps the body kick into high gear almost instantaneously by increasing the heart rate and blood pressure. Cortisol’s effects are observed over the longer−term: blood sugar rises and fat and protein stores are mobilized to help replenish lost energy as it is needed.

The following sections are intended to illustrate some of the health issues associated with chronic stress, illustrating both the behavior and the biology behind them.

As the everyday stressors of life seem to be continually on the rise – from work and unemployment concerns to family and health issues – so does the collective waistband of the U.S. population. Is there any physiological relationship between stress and weight, or is it all in our heads, so to speak? The answer is a little bit of both.

The fact that stressed−out people often overeat is no secret. We’ve all done it at one time or another – reaching for a bag of chips to calm our frazzled nerves is not a completely foreign concept to most people. Studies have shown that men and women both pack on pounds in response to stressful life circumstances, though the triggers may be very different. One study found that for women, the stressors that were linked to weight gain were more varied than for men, and consisted of everything from family to financial problems. For men, on the other hand, lacking the ability to make decisions or to be creative at work was associated with more weight gain.

But there is an additional reason that we tend to gain weight when chronically stressed, and this has to do with how the metabolism is affected by the presence of cortisol over the long term. Over time, high levels of cortisol in the system can wreak havoc on the way the body metabolizes energy.

But there is an additional reason that we tend to gain weight when chronically stressed, and this has to do with how the metabolism is affected by the presence of cortisol over the long term. Over time, high levels of cortisol in the system can wreak havoc on the way the body metabolizes energy. As mentioned earlier, the hormone is in charge of increasing blood sugar levels to replenish lost energy stores. But when long−term stressors are present and cortisol levels remain elevated, blood sugar and therefore insulin levels also remain high. This situation not only leads to unwanted weight gain, but, if left unchecked, can ultimately lead to type 2 (adult onset) diabetes. If you find that you are over−eating chronically, particularly in response to certain stressors, it’s a good idea to step back and determine whether any of these factors can be removed from the picture, or if not, what a more effective approach to dealing with them might be.

It may come as no surprise that stress and depression are intimately connected, both behaviorally and physiologically. Long−term stressors, like unemployment, family issues, or health problems can easily push one from the realm of stress into the murky, uncomfortable territory of depression. As always, these changes in behavior – as stress becomes depression – are not only psychological in nature, but also have significant and complex physical underpinnings as well.

Rats, who provide researchers with an excellent model system to study stress and depression, when chronically injected with stress hormones, develop classic symptoms of depression.

People who suffer from depression have lower levels of certain brain chemicals that underlie the disorder (the most familiar of which is serotonin, part of a group of neurotransmitters). Studies have also shown that people suffering from full−blown depression secrete cortisol at much higher rates than the normal individual. In depressed individuals, which event comes first – high circulating cortisol or low levels of the brain chemicals involved in depression – is a bit of a chicken−or−egg dilemma that is still somewhat unclear. But there is some good evidence that abnormally high cortisol levels may actually be the initial culprit in many individuals. In fact, rats, who provide researchers with an excellent model system to study stress and depression, when chronically injected with stress hormones, develop classic symptoms of depression.

One reason that stress often precipitates depression is that the two systems are biologically interrelated. Some researchers believe that chronic stress not only raises cortisol levels, but it also produces significant, measurable changes in the brain’s monoamine system, which consists of a large group of neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin and is frequently the target for antidepressant medications. Cortisol, the primary long−term stress hormone, also appears to affect serotonin activity, which is perhaps the most important neurotransmitter involved in depression.

A classic piece of evidence for the hypothesis is the fact that people suffering from Cushing’s disease, in which stress hormone levels are chronically elevated, often suffer from depression as well, making initial diagnosis tricky for clinicians. Additionally, it’s been known for some time that certain anti−depressant drugs not only work to increase serotonin levels in the brain, but they also appear to have an effect on the activity of the HPA axis, reducing cortisol levels in the process. If one is feeling symptoms of depression lasting more than a couple of weeks, it is a generally good idea to talk to one’s health care provider about appropriate steps to take to address them.

Sometimes the individual may not even be aware of developing ischemia, in which case it is considered to be “silent.” However, it is thought that silent ischemia can lead to full−blown heart attack, made even more likely by the fact that people who suffer from it, because they are unaware of it, would not seek treatment or make the appropriate changes to their lifestyles to reverse it.

Many of us have probably had the unfortunate experience of forgetting something crucial at an inopportune moment – like during an important presentation or job interview. Under these stressful circumstances, the mind can draw a “blank,” and information that would normally be easily retrieved can be forgotten. This is because one of the adverse effects of the stress response is memory loss – more specifically, both memory formation and memory retrieval can be disrupted considerably (and frustratingly) during these times.

One of the brain regions that is asked to forgo adequate blood sugar during stressful events is the hippocampus, which is key area in the formation of new memories.

Chronic stress interferes with our ability to form new memories, in other words, it can be an obstacle to, learning. That's because during the stress response, as cortisol prepares the body to fight or flee, one of its duties is to redirect blood sugar to the large muscles so that they may react swiftly. But since there is a finite amount of energy reserve in the body, other areas must “sacrifice” blood sugar, and, unfortunately, the brain is one of these. One of the brain regions that is asked to forgo adequate blood sugar during stressful events is the hippocampus, which is key area in the formation of new memories. Animal studies have also confirmed that noticeable anatomical changes occur in the hippocampus after a period of chronic stress. Rats subjected to three weeks of chronic stress had significant changes in the synapses of the brain (the spots where nerve cells nearly touch and release compounds to communicate with one another). In an example closer to home, veterans suffering from post−traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have also been shown through MRI to have smaller hippocampi than healthy participants. In fact, the smaller the hippocampus, the poorer the veterans’ short term verbal memory, which underlines the link between hippocampus volume and memory formation.

But there is more to memory than its formation. As the example of going blank in a job interview or other stressful situation illustrates, memories need not only be stored, but they must also be retrieved – or accessed – to be of any use to us. Not surprisingly, cortisol also appears to adversely affect our ability to retrieve information stored in our memories. In one study on healthy young (human) males, participants were intentionally stressed out in the laboratory, using a method in which the participant must make an impromptu speech and then carry out mental arithmetic in front of a panel. Cortisol levels were then measured and memory retrieval of a previously memorized word list was tested: those subjects who had performed stress test had significantly higher cortisol levels than control participants and they also performed significantly worse on the memory retrieval test. The study provides a nice illustration of the ill effects of even a single instance of stress on the retrieval of remembered information.

During stressful times, many people notice that sex is the last thing on their minds. Clearly this phenomenon is somewhat related to one’s drive to prioritize: when paying bills, searching for a job, tending to the children, or dealing with an illness, sex tends to fall by the wayside as those other, more pressing occupations come to the forefront. So while lack of sex drive might appear to be a largely psychological dilemma, there is, as always, also a biological reason behind the phenomenon – and one of the main culprits, not surprisingly, is cortisol.

In men, cortisol also acts to inhibit the process by which testosterone is created from its components, which leaves a male with low levels of circulating testosterone. Even more than this, cortisol suppresses the ability of the male sex organs to respond to testosterone’s libido−enhancing effects...

In our fight or flight example, it may not come as a shock that the last place the blood supply is going is to the genitals (when in a perilous situation, it’s generally a good idea to concentrate on the task at hand, rather than stopping to have sex). But in men, cortisol also acts to inhibit the process by which testosterone is created from its components, which leaves a male with low levels of circulating testosterone. Even more than this, cortisol suppresses the ability of the male sex organs to respond to testosterone’s libido−enhancing effects, which leaves a stressed−out man with a lower−than−normal drive for sex.

Women also feel the effects of the suppressed libido as a result of stress, partly for the reasons mentioned above: testosterone also plays an important role in the female sex drive, though this is less widely known than the roles of the two major female sex hormones, estrogen and progesterone. These hormones also take a hit from high cortisol levels. Plummeting estrogen and progesterone can send a woman into a condition called amenorrhea, in which the menstrual cycle ceases completely for a period of time, or, alternatively, a woman’s cycle can become irregular from these disruptions in hormones levels. In both cases, the female libido can become seriously diminished as a result of reduced sex hormone circulation. Clearly fertility is severely compromised or obliterated completely during these times, until a healthy menstrual cycle is restored. The good news is that resuming a normal cycle is absolutely possible, provided that the stressors causing the problem in the first place are addressed.

In the most extreme scenarios, people who suffer from PTSD often have significant problems with libido. It seems logical that the more severe the stressor, the more one’s mental and physical reserves are being diverted to the stimulus causing the stress, and the less these reserves are going into maintaining a healthy sex drive. Stress exerts its effects in many ways, and behaviors that we often take for granted – like libido – often fall prey to these effects, particularly over the long term.

The effects of sleep deprivation can be devastating to our daily lives, regardless of whether stress is involved or not. Even one night of lost or fitful sleep can wreak havoc on the way we function the following morning, leaving us in a fog, and feeling like our actions are less effective than they might be under well−rested circumstances. Though stress isn’t always the culprit behind sleep−deprivation it can certainly play a role in our sleep patterns.

One study found that in healthy individuals, a night of partial or total sleep deprivation accounted for rises in cortisol level the next day of 37% and 45%, respectively, as compared to people who got full nights of sleep.

Cortisol is known to interfere with sleep, and studies have shown that people who suffer from chronic insomnia have significantly higher levels of cortisol as well as adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), the compound responsible for increasing cortisol production. What’s more, as people age they may become more sensitive to the effects of stress hormones than younger people: one study administered to male participants a compound called corticotrophin−releasing hormone (CRH), which stimulates stress hormone secretion. The study found that the sleep patterns of the older males were significantly more disrupted than those of the young men, even though the levels of cortisol and ACTH in the two age groups were similar, which suggests that middle−aged men were more susceptible to the effects of stress hormones than younger men.

Even more frustrating is the fact that there appears to be an unfortunate cyclical relationship involved in stress hormones and sleep. One study found that in healthy individuals, a night of partial or total sleep deprivation accounted for rises in cortisol level the next day of 37% and 45%, respectively, as compared to people who got full nights of sleep. The researchers concluded that this phenomenon leads to a disruption in normal HPA axis function, and may actually stimulate the stress response. So, not only does elevated cortisol lead to sleep disturbances, but sleep disturbances can actually increase cortisol levels the following day, creating a potentially vicious cycle of stress and sleep deprivation.

If the message that chronic stress is bad for the mind or body weren’t clear enough from the sections above, it might be useful to mention that stress also has an adverse affect on overall health. More specifically, stress can affect the function of the immune system, the body’s natural means of fighting off infection. Compounds called cytokines, are secreted during the body’s immune response, and increased blood levels of the compounds are a telltale sign that the body is in the process of fighting infection. Chronic stress has been found to disrupt the normal immune response: now cytokines may be chronically present in the system, but rather than acting to heal the body, chronic inflammation may result instead. Inflammation is thought to underlie a laundry list of more serious disorders and diseases, including heart disease, diabetes, and some forms of cancer.

Though many people use the term “stressed out” somewhat loosely to describe their state of being at the moment, feeling stressed mentally and physically is a serious concern, as should be evident from the number of complications that can result from chronic stress. Whether feelings of stress are new or have been felt over a long period of time, it’s important to address these concerns, and find ways to relieve the underling stressors for the long term. It may be a good idea to consult your health care provider to discuss the cause/s of your stress and begin to determine specific approaches to reduce it. Coping with stress will be the next topic in our series on the subject.