Targeting sleep health may be a workable approach to catching Alzheimer's early and eventually, preventing it or reducing its impact, a new study suggests. Alzheimer's Disease (AD) is a chronic and progressive neurodegenerative disease that is currently untreatable. It is the cause of 60 to 70 percent of dementia, affecting memory and reasoning, and leads to loss of vocational, social, self care skills and control over bodily functions.

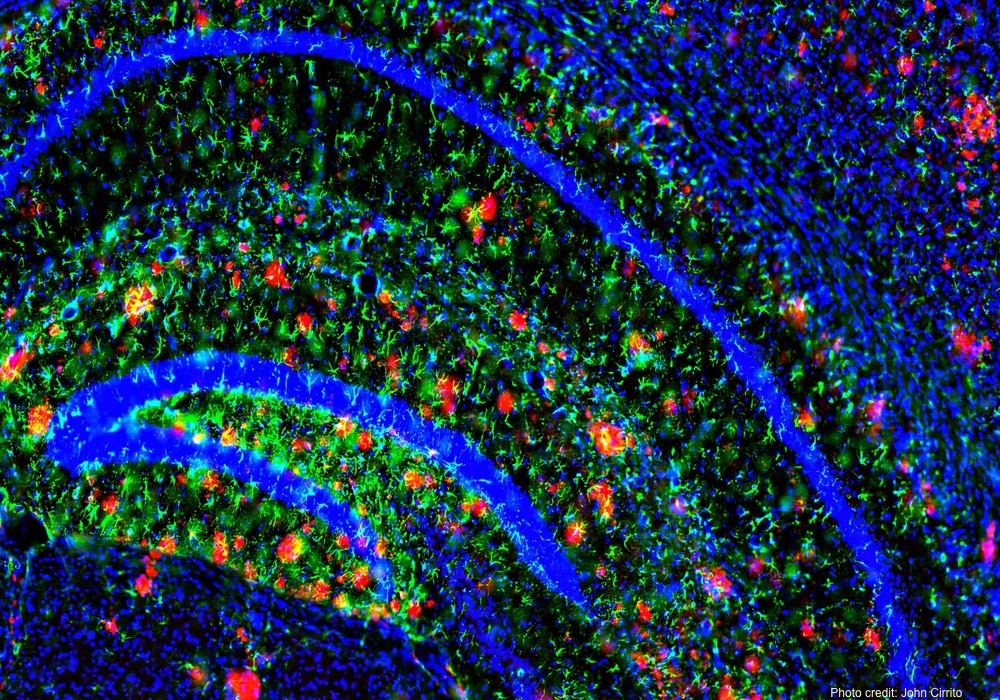

Although the cause remains unknown, the disease is associated with abnormal amyloid plaque deposits and tangles of tau proteins in the brain.

These abnormalities can be seen on PET scans of brains of AD patients. Unfortunately, by the time the symptoms of Alzheimer's show up, the disease has usually already disrupted brain function. The value of early detection has led to the search for biomarkers of the amyloid and tau proteins in the cerebrospinal fluid and used in research to identify the presence of the disease even before the patient experiences symptoms.

A recent study used this technology to look at the relationship between sleep and these cerebrospinal fluid markers of amyloid and tau deposition. Based on previous studies, the researchers wanted to see if poor sleep was associated with more amyloid markers in cerebrospinal fluid, and by extension, an increased risk of developing Alzheimer's.It is not clear that the poor sleep causes the increase in amyloid and tau proteins. It is possible that these abnormalities in the brain are causing the disrupted sleep.

The investigators followed 101 patients, ages 56-68, all of whom had normal brain and memory function at the start of the study. All had either a family history of AD, or were known to carry the gene that increases the susceptibility to AD. Data were controlled for age, sex, medical history, depression, BMI, family history and other conditions that might affect the results. Participants' were asked to provide self reports of their sleep quality, which was also assessed using standardized questionnaires. The researchers performed spinal taps to evaluate the cerebrospinal fluid biochemistry of participants.

Those patients with poor reported sleep quality showed more evidence of Alzheimer's-associated amyloid and tau biomarkers in their cerebrospinal fluid even in the absence of symptoms. The researchers believe this supports the idea that sleep quality and AD are related and that biomarkers for amyloid and tau proteins in cerebrospinal fluid are viable early markers for brain changes that are occurring before Alzheimer's is clinically apparent.

The study does not prove cause and effect. That is, it is not clear that the poor sleep causes the increase in amyloid and tau proteins. It is possible that these abnormalities in the brain are causing the disrupted sleep. However, other research suggests that poor sleep may indeed contribute to the increased production, reduced removal and the deposition of the Alzheimers-related proteins in the brain.

Sleep is known to be a form of mental housekeeping and important in the maintenance of the neural connections within the brain. Delaying the onset of Alzheimer's, even by a few years, would be a valuable contribution to individual and public health.

Though the exact relationship is not yet clear, one idea is that poor sleep alters brain neurochemistry by disrupting the normal rhythms and release of growth and stress hormones. Poor sleep may also directly lead to increased production of amyloid or reduced removal of amyloid proteins in the cerebrospinal fluid, an idea supported by animal studies.

The study is published in Neurology.