Everyone's experienced rage at one time or another. From furious disagreements with family members or significant others to political arguments to road rage and violent assault, people sometimes lose all control of themselves. But what causes it? Researchers working with mice have now found that one part of the brain appears to play a major role.

“Our latest findings show how the lateral septum in mice plays a gatekeeping role, simultaneously ‘pushing down the brake’ and ‘lifting the foot off the accelerator’ of violent behavior,” Dayu Lin, the senior author of the study, said in a statement.

This rage — sudden, violent acts, mostly attacks on other mice — has long been seen in rodents and some birds with a damaged lateral septum. But details of the process have been elusive.Researchers found they could start, stop and re-start aggressive outbursts in the mice.

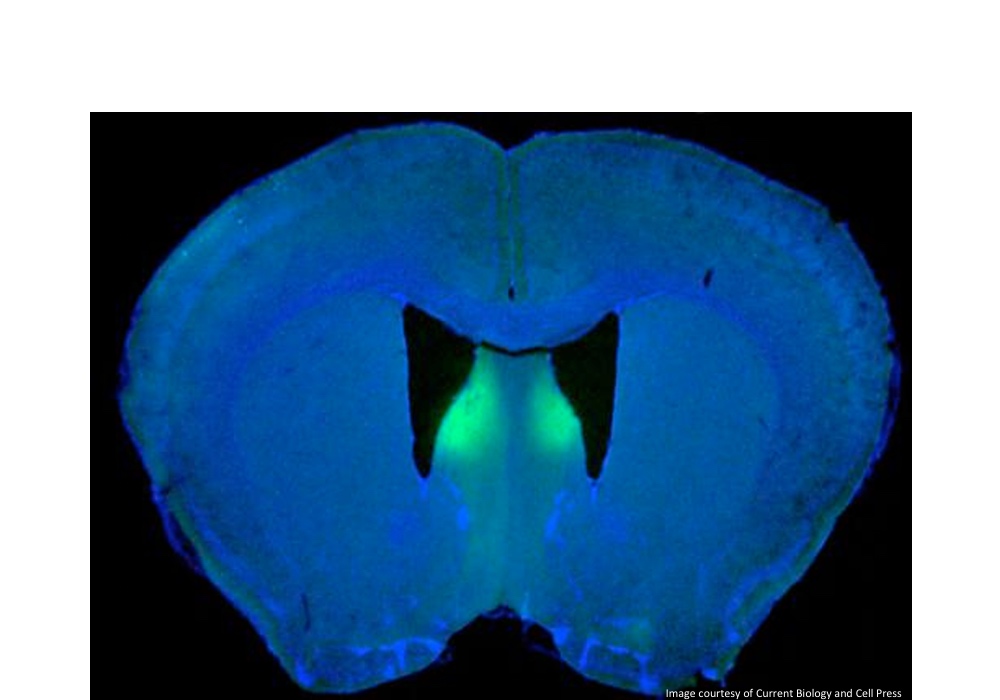

The researchers found that they could start, stop and re-start aggressive outbursts in the study mice by exciting selected groups of brain cells in the lateral septum with light from a surgically inserted probe which changed the activity of these cells.

The lateral septum appears to accomplish this by interacting with another part of the brain that it is physically connected to, the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus is intimately involved in hormone production, among other functions, and mice need one part of the hypothalamus, the ventrolateral ventromedial portion, to be intact for aggression to occur.

The gate-keeping aspect of the lateral septum came to light when researchers noticed the cells most active during mouse attacks were the ones suppressed to the greatest extent by the lateral septum, while the cells that the lateral septum activated were those that had been suppressed during the mouse attacks.

This suggests that the lateral septum uses a two-pronged approach to lower or halt aggression, suppressing attack-excited cells while activating attack-inhibited cells. Lin calls this being a smart gatekeeper.

“Our research provides what we believe is the first evidence that the lateral septum directly ‘turns the volume up or down’ in aggression in male mice, and it establishes the first ties between this region and the other key brain regions involved in violent behavior,” said Lin.

Septal rage is not known to occur in humans, she added, but studying male aggression in mice might help to map the circuitry that is involved in controlling violent behavior in humans.

The team's long-term goal is to determine whether therapeutic means can be found to control aggression without compromising social and cognitive abilities.

The study appears in Current Biology.