For years, one of the traditional remedies of rural people in Southern Italy and other parts of the Mediterranean has been a tea made from the leaves of the European chestnut tree which is used by healers who wash the skin with it to treat infections and inflammation.

Now it appears that the humble remedy can effectively stop a dangerous bacteria that has proven to be extremely resistant to antibiotics.

Despite the fact that many drugs were originally isolated from plants, such folk remedies often get little respect from scientists, almost as if they were promoting eye of newt and toe of frog.The mice injected with the chestnut leaf extract remained uninfected, as seen in the images in the far left column at the top of the page.

“I felt strongly that people who dismissed traditional healing plants as medicine because the plants don't kill a pathogen were not asking the right questions,” she said. “What if these plants play some other role in fighting a disease?”

So Quave and her team began steeping chestnut leaves in various solvents. After a massive amount of work, they ended up with extract 224C-F2.

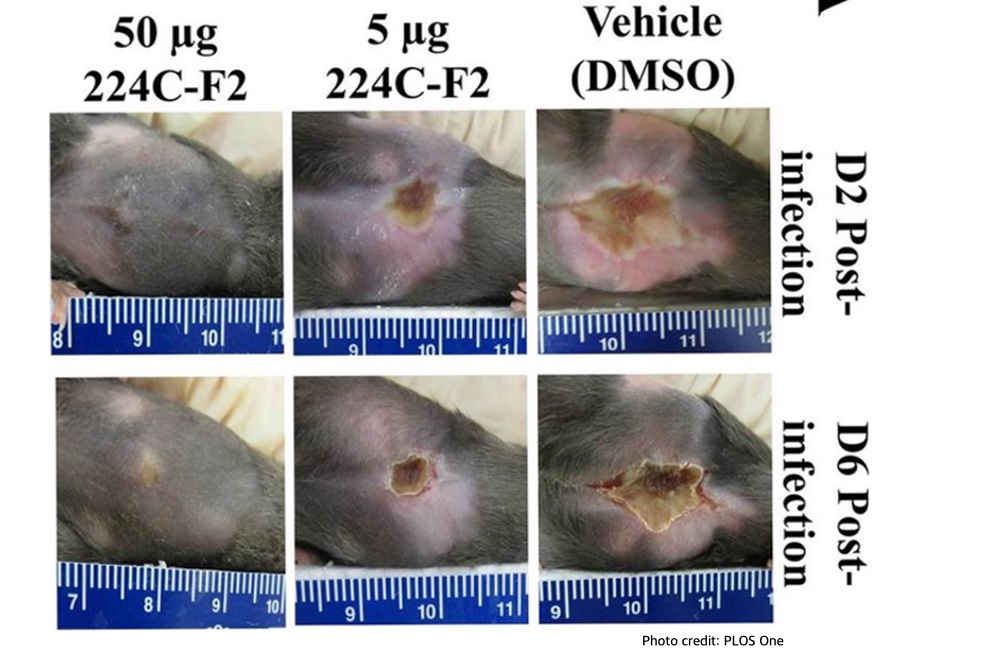

Quave's team injected 50 micrograms of this extract into mice at the same time that they infected them with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA, a bacteria that eats away at the skin and has proven extremely resistant to antibiotics. The mice did not suffer the skin, tissue and blood cell damage that other infected mice treated with only the solvent DMSO did.

Essentially, the mice injected with the chestnut leaf extract remained uninfected, as seen in the images in the far left column at the top of the page.

As Quave explains, “Rather than killing staph, this botanical extract works by taking away staph's weapons, essentially shutting off the ability of the bacteria to create toxins that cause tissue damage. In other words, it takes the teeth out of the bacteria's bite.”

The chestnut leaf extract does not harm mouse skin or human skin cells grown in the laboratory or the collection of bacteria that is normally present on human skin.

Even better, because the extract does not kill or even slow the growth of Staph aureus bacteria, it puts no obvious pressure on the bacteria to develop resistance to it. While the researchers were only able to test this for a few weeks, they found no evidence of resistance developing in extract-treated bacteria.

More research is needed to determine whether 224C-F2 will work as a stand-alone treatment for people with infections. But there are still plenty of possibilities for it, from use alongside current antibiotics or as a spray to prevent infection on everything from athletic equipment to medical instruments.