The great thing about science is that it’s always building upon itself. And sometimes this means reevaluating what we thought we knew, even about something as seemingly straightforward as cholesterol. Researchers have just discovered that a long-held assumption about how cholesterol and inflammation interact is not quite accurate – a discovery that could lead to new treatments.

It was believed that the accumulation of cholesterol inside cells triggers an increase in the genes that cause inflammation, which is ultimately what sets in motion the plaque build-up in the arteries -- atherosclerosis. Now a team of researchers at the University of California at San Diego has found that too much cholesterol may actually reduce expression of these inflammation-producing genes.

When the normal function of desmosterol is compromised, the system breaks down and the damaging effects of high cholesterol occur.

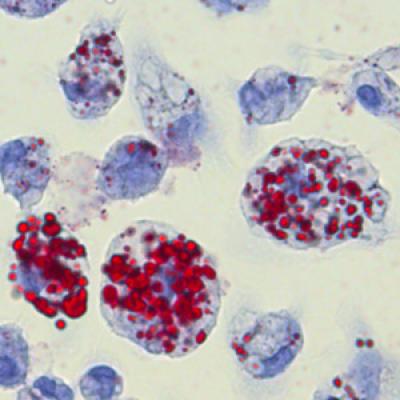

Macrophages are one type of the body’s immune cells – they engulf and devour foreign matter, including cholesterol (see photo). "When they do that,” said study author Christopher Glass in a news release, “it means they consume the other cell's store of cholesterol. As a result, they've developed very effective ways to metabolize the excess cholesterol and get rid of it."

Credits: Image courtesy of Marten Hoeksema, University of Amsterdam

The problem occurs when these effective methods break down. When this happens, cholesterol accumulates inside the macrophages as fatty or foamy droplets, which turns them into macrophage foam cells. Researchers used to think that these foam cells increased the inflammatory response, but the researchers discovered, by studying a mouse model of the cholesterol pathway, that they actually turn off these inflammatory genes.

The team also discovered that a precursor to the cholesterol molecule, called desmosterol, helps macrophages know how to deal with excess cholesterol and turn off the cholesterol-making process. When the normal function of desmosterol is compromised, the system breaks down and the damaging effects of high cholesterol occur.

These discoveries open up new avenues for the treatment of atherosclerosis, which kills tens of thousands of people per year, according to the study. In the 1950s, a drug that boosted desmosterol levels was introduced, but taken off the market shortly after because of serious side effects (including the development of a rare type of cataract that caused blindness). Luckily, there’s a synthetic version of desmosterol available today, which could undergo testing shortly.

"We've learned a lot in 50 years," said Glass. "Maybe there's a way now to create a new drug that mimics the cholesterol inhibition without the side effects."