Most of us think our taste for a white bread, low-fiber diet is our own business, and that we're not hurting anyone but ourselves. Unfortunately, your love of white flour and processed foods can actually harm the digestive health of your grandchildren, your great-grandchildren, and their children.

It seems hard to believe, but not eating enough fiber doesn't just disrupt the digestion of the person choosing the soft loaf of bread at the supermarket, but, over generations, is responsible for the extinction of certain beneficial bacterial systems in the gut, according to new study from the Stanford School of Medicine.The colonization of intestinal bacteria begins even before you were born. It continues to evolve as you age.

Once these key bacterial species are gone, there may be no amount of “eating right” that can restore them.

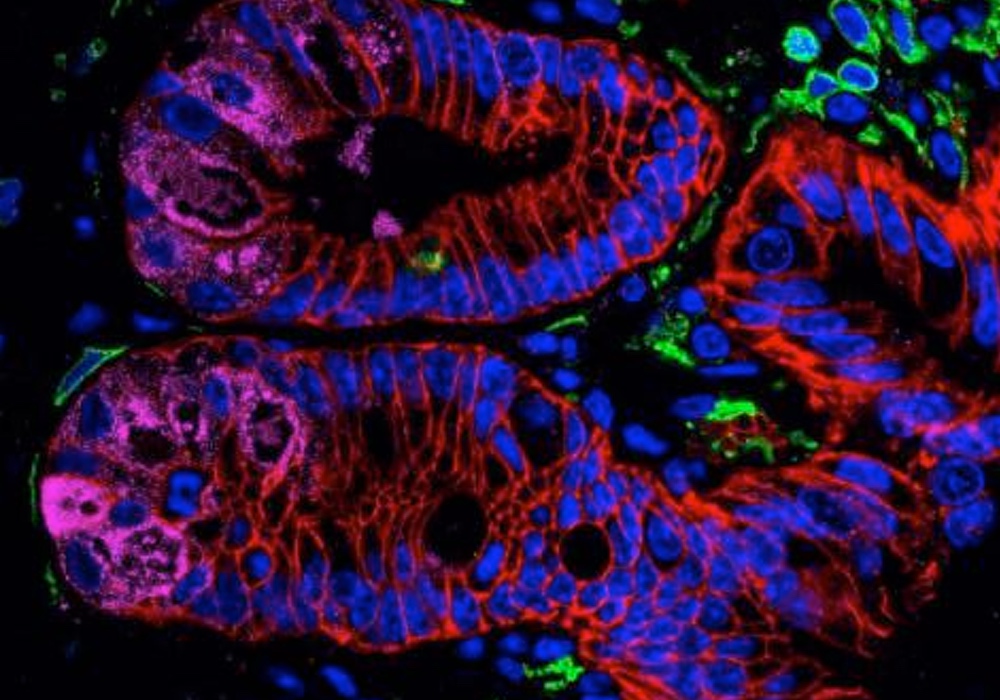

The bacteria in our bodies, our microbiota, are essential. Thousands of different species live in the large intestine. They aid in the digestion of foods that the stomach and small intestine are unable to digest on their own. They are also necessary for the synthesis of certain vitamins.

The right balance of bacteria in your gut ensures proper functioning of your digestive system. Our bodies' bacteria form a barrier to protect your immune system from invasion by harmful bacteria, and they aid in keeping the lining of your intestinal tract healthy.Your immediate family is the most significant source of intestinal bacteria, especially your mother during childbirth and infancy.

Your immediate family is the most significant source of intestinal bacteria, especially your mother during childbirth and infancy.

One group was fed a high fiber diet, and the other group was fed a diet with practically no fiber, but the protein, fat, and calories in both diets were the same.

Seven weeks later, the mice on the low-fiber diet were switched to a high-fiber diet for four weeks. Though their gut-bacteria recovered somewhat, they were not completely restored. A third of the original microbial species never recovered.Several generations later, mice that had been bred and fed low-fiber diets and only exposed to microbes through contact with their parents, lacked nearly 75 percent of the bacterial species that were present in the guts of their great-grandparents.

The mice that were fed a high-fiber diet from the beginning experienced no such changes to their gut bacteria.

Several generations later, mice fed low-fiber diets and only exposed to microbes via contact with their low-fiber-fed parents lacked nearly 75 percent of the bacterial species that were present in the guts of their great-grandparents. When they were fed a high-fiber diet, over two-thirds of the bacterial species present in the first generation mice were found to be extinct.

The researchers then tried to restore the composition and diversity of bacteria in the fourth-generation mice eating a low-fiber diet by transplanting microbes from the mice eating a high-fiber diet into the guts of fourth-generation mice on a low-fiber diet. This, and switching them to a high-fiber diet for two weeks, restored their gut bacteria profiles completely within 10 days.

The implications for humans are pretty clear. The huge growth of processed convenience foods that are practically devoid of fiber has reduced the average person's fiber consumption to about 15 grams per day per person, about half of what is recommended.Women should consume 25 grams of fiber per day; men need 38 grams per day. The best way to meet those goals is to eat more plant foods — fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and nuts.

Health experts agree that diets lacking in fiber are substandard, and fiber is the main source of food for the bacteria that reside and colonize in our colons.

Women should consume 25 grams of fiber per day; men need 38 grams per day, according to the Institute of Medicine. The best way to meet those goals is to eat more plant foods — fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and nuts. Avoid refined grains as much as possible, and replace them with whole grains, such as whole wheat bread, whole oats, whole grain flours, and brown rice.

The study is published in the journal, Nature.