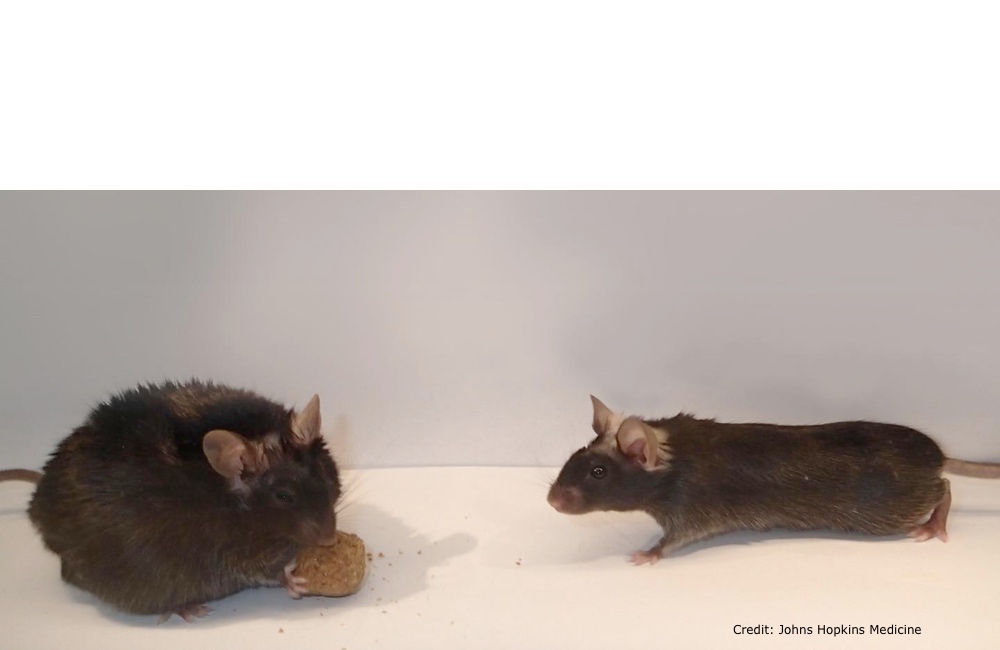

There may be special cells in the brain that take over when you encounter a buffet — and other occasions — and find it hard to stop filling your plate, according to a mouse study that has the pictures to back it up (see photo above).

The researchers appear to have found an entirely new signaling system that tells people to stop eating when they're full. When these signals are blocked, mice, at least, ate much larger meals, consuming enough extra calories to double their weight in three weeks.

The study authors were originally more concerned with structural engineering than with diet. They were interested in the role of a small molecule called n-acetyl glucosamine (GlcNAc) on the strength and integrity of synapses. Synapses are the parts of nerve cells that produce neurotransmitters, chemicals that allow one nerve cell to communicate with others.The mice doubled their weight in three weeks. And it wasn't through bodybuilding — fat buildup, not muscle, was responsible.

To get a better idea, the researchers looked at what would happen if nerve cells in the mouse brain couldn't put GlcNAc on any of their proteins. They did this by eliminating a gene controlling GlcNAc.

They soon had some extremely fat mice on their hands.

These mice doubled their weight in three weeks. And it wasn't through bodybuilding; fat buildup, not muscle, was responsible.

When the researchers examined the eating behavior of the fat mice, they found that they were eating the same number of meals as their normal weight counterparts but were lingering longer and eating more at each meal. When they were forced to eat a normal amount of calories, they stopped gaining weight. So it seems their problem was not knowing when they were full and continuing to eat.

A closer look led the researchers to a small set of nerve cells in an area of the hypothalamus called the paraventricular nucleus. These cells had very few incoming synapses, about a third of what you'd normally expect. They also didn't fire very often. Perhaps they were missing signals that would normally cause them to fire?

To show that these cells were actually involved in (eating behavior), the researchers altered them so that they would fire when stimulated with a blue light. When they did so, increasing the rate of firing caused the mice to eat about one-third less.

This suggests that the fat mice did indeed have a signaling problem. And that these particular cells in the hypothalamus were involved.

This appears to be an entirely new signaling system, distinct from other known appetite signal systems such as leptin and ghrelin. If other studies confirm these results, it might go a long way towards explaining why so many people continue mindlessly eating after they've already had enough. And maybe it will lead to a better way to help people who need to eat less do so.