Financial transactions are often difficult for seniors. It may be that they're slow counting change in the check out line. They are also vulnerable to billing scams in which fraudulent entities prey on the memory issues facing aging adults and demand payment for bills that have already been paid.

Seniors' ability to manage their money can serve as an early warning sign of dementia, a team of researchers from Duke University finds. In fact, it can be used to assess how robust their memories are. The 20-minute Financial Capacity Instrument-Short Form used in the study could serve as a way for doctors to track even subtle changes in a person's cognitive function over time.

“There has been a misperception that financial difficulty may occur only in the late stages of dementia, but this can happen early and the changes can be subtle,” said P. Murali Doraiswamy, a professor of psychiatry and geriatrics at Duke and senior author of the paper. “The more we can understand adults' financial decision-making capacity and how that may change with aging, the better we can inform society about those issues.”The Financial Capacity scale could help doctors discover memory deficits earlier and counsel their patients before problems became more advanced.

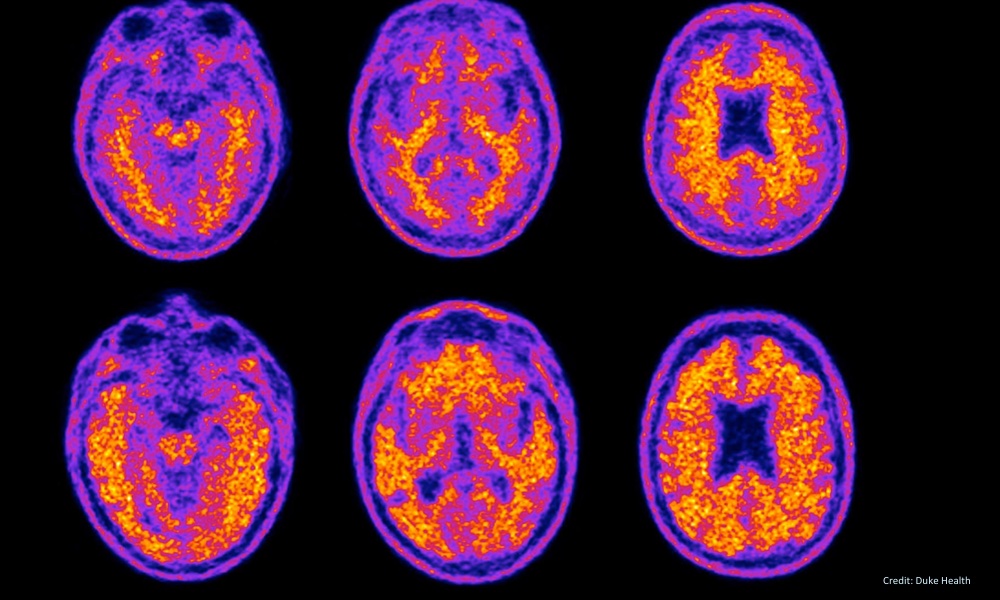

The financial skills of all the people in the study were tested and their brains scanned to determine the extent, if any, of beta-amyloid plaque protein buildup, a sign of Alzheimer's disease. The image above shows brain scans of two study participants. The top row is a scan of the brain of a cognitively healthy 74-year-old who demonstrated average financial skills. The bottom row shows the scan of an 86-year-old with mild Alzheimer's disease who had impaired financial skills. The yellow and orange throughout the lower scan indicates the presence of amyloid plaques.

Certain financial skills declined with age and showed up at the early stages of mild memory impairment, the team found. Men and women showed similar types and levels of difficulty when it came to calculating balances or understanding basic financial exchanges, even after controlling for a person's education and other demographics.

The more extensive the amyloid plaques were, the more difficulty a person had when it came to grasping financial concepts. Doraiswamy cautions that even cognitively healthy people can develop protein plaques, but they tend to appear earlier and are more widespread among those with a family history of cognitive impairment.

“Older adults hold a disproportionate share of wealth in most countries and an estimated $18 trillion in the U.S. alone,” Doraiswamy said. “Little is known about which brain circuits underlie the loss of financial skills in dementia. Given the rise in dementia cases over the coming decades and their vulnerability to financial scams, this is an area of high priority for research.”

The study is published in The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer's Disease.