Opioid addiction and overdose deaths are up all over the United States. Prescriptions for opiate painkillers often serve as the gateway to the use of illicit, non-prescription drugs like fentanyl that tend to be cheaper than prescription opioids. The risk of addiction, overdose and death increases as prescription opioids are taken in higher dosages for longer periods of time or as extended-release and long-acting formulations. The length of time a person uses opiates is the strongest predictor of opioid use disorder and overdose.

There are big differences among states in the number of opioid-related overdoses, subsequent emergency department visits, hospital use and deaths, a study by researchers from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found.

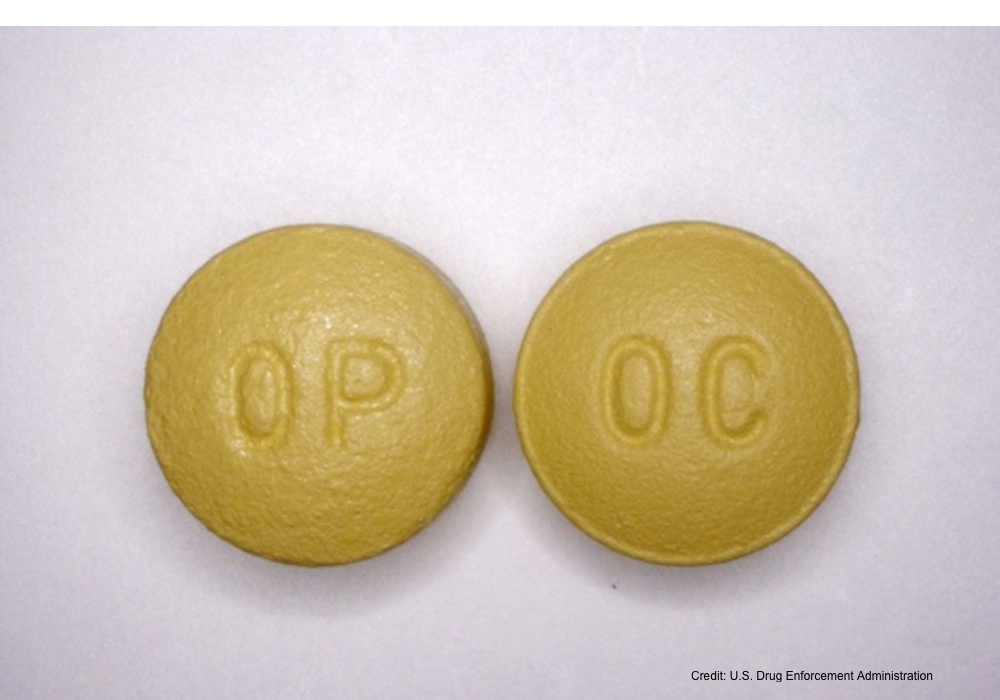

States have the authority to establish and fund state-and county-level intervention programs, and they can also establish policies and pass legislation restricting opioid use. The CDC study's analysis of opioid prescriptions filled at U.S. pharmacies over 12 years — between 2006 to 2017 — suggests that state-level regulations could change the picture considerably.The duration of a prescription for opioids is the strongest predictor of opioid misuse and overdose. Unused pills may be diverted to the streets for sale.

The picture was a little less rosy when the researchers looked at the duration of opioid prescriptions, considering the number of prescriptions lasting three days or less and those lasting 30 days or more. They also studied the number of prescriptions written for a high daily dosage and those for extended-release and long-acting formulations.

Short-term, prescriptions (defined as three days or less) decreased significantly in 48 states, and the number of prescriptions for long-acting and extended-release formulations also dropped significantly in 27 states.

The increase in average duration per prescription and the prescribing rate for prescriptions of 30 days or longer are worth further study, Schieber believes. The researchers didn’t look specifically at why the opioid prescriptions were being written for longer periods of time, but studies have shown duration of use is the strongest predictor of opioid misuse and overdose. In part this is because unused pills may be diverted to the streets for sale. “Prescription opioids are often the gateway for heroin users,” Schieber said.Short-term prescriptions for opioids decreased, but long-term prescriptions increased.

“Best practices for opioid prescribing are still not well understood,” she added. The goal is to reduce the use of opioids in favor of non-opioid pain management, while still providing prescription opioids for those who really need them.

“Because duration of use is the factor most often associated with opioid use disorder and overdose, the increase in mean duration per prescription and prescribing rate for 30 or more days is notable and worth further investigation. However, the decline in short-duration prescriptions may indicate a growing awareness by prescribers that non-opioid medications and other pain-control measures, such as exercise and cognitive behavioral therapy, can be effective for short-term pain relief,” the authors write.

The study is published in the JAMA Network Open.